Making Room for people with chronic illnesses

Update, 20 Apr 2022: The recording of the talk is now available to watch on the GDC Vault

This is a rough transcript of a talk I gave at GDC 2022, as part of the “Making Room” track. So it’s written in a this-is-for-speaking style, and you should imagine the headings as slide transitions. OK! Let’s go:

Hello, I’m v buckenham, and today I’m going to be talking about chronic illness and what you can do to support any of your employees who have a chronic illness.

So, first things first, I should say now that I’m going to be focusing on my own experiences as someone who has a chronic illness, as that’s what I know best.

[spoiler warning]

- ask people what they need

- build an environment of trust

And as a spoiler warning for the end of the talk, I should say more broadly the important thing is to listen to your employees and find out what they need. And to build an environment of trust so that they will actually tell you about what’s going on and what that is.

And the other thing I should say upfront is that my experiences are not unique.

60% of Americans have at least one chronic illness

So depending on how you define it, about 60% of adult Americans are living with at least one form of chronic illness. Chronic illness can last from several months to a lifetime and can take many forms: Long Covid, arthritis, musculoskeletal pain, diabetes, asthma, migraines, blood disorders, cancer, heart disease, irritable bowel syndrome, autoimmune diseases, and a range of mental illnesses like depression, anxiety. the list goes on.

So. Let me tell you my story.

My Story

I’ve worked in videogames for about a decade, much of that time in small teams, and in indie spaces. I’ve put on games events, including being part of organising That Party here at GDC with Wild Rumpus. I worked on a game called Mutazione for a few years, then joined a startup making a weird digital physical stacking game called Beasts of Balance, for which I did the majority of coding & game design for. We were eventually acquired by Niantic (who make Pokemon Go), where I worked as a lead designer.

So August 2020, the pandemic had hit, everyone was working from home. Obviously a weird time in general, but I was dealing okay… until one Monday morning, I woke up, got ready, sat at my desk for our normal morning let’s-start-the-week meeting, and found I was kind of sliding out of my chair a bit. I’d had a migraine earlier in the year and the after effects from that were kind of similar feeling, so I wondered if it was something like that, and moved to my bed to keep working. An hour or so later, it was clear I wasn’t really in any kind of state to do work. And then found I wasn’t really in a good shape at all. All in all, I basically spent the next month or so in bed other than medical appointments and for quick trips to the toilet and to the kitchen.

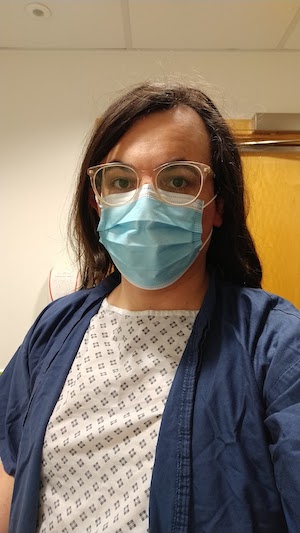

I had a lot of investigations done

(here’s me in a hospital gown about to get an MRI scan)

but none of them turned up anything concrete that would explain the fatigue.

And at this point I’m still after all this time trying to chase down a proper diagnosis, but my assumption at this point is that I have Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, which is a “diagnosis of exclusion” - basically, when you are suffering from fatigue, have been for a while, and there’s no other good reason why. My symptoms seem especially triggered by being upright - standing, walking, even sitting up in a chair. Which means I also suspect PoTS, which stands for Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome. This is basically where your heart doesn’t respond appropriately to the extra challenge of pumping blood all the way from the feet up to your head. Which it turns out is more effort than pumping it around when everything is on the same level. The primary symptom I get is what’s called “brain fog” - when this is bad, I can feel my eyes unfocusing, my attention starting to slide off things, my capacity to, just… think about things goes away. And this also means frustration with memory, just lots more of those “tip of the tongue” feelings. I know this, I knew this, but—

And I should say that this was really scary. It turns out a lot of my self identity was built up around being a person who can do this work, who is a sharp thinker, who exists in the world, who can run around plugging cables into things at events. It’s really scary to not know what level of function you will regain, to not know if you will be able to do those things again. Ever, maybe.

Over time, I’ve slowly improved a little - after a month or two (and when my sick leave had ran out), I returned to work, although initially on reduced hours, and only slowly picked up the responsibilities I had beforehand. Around Christmastime that year, my health had improved to the point that I could go for like, half hour walks in the park nearby, as long as I could sit on benches along the way and rest.

And this is pretty much the state I’m still in now, 19 months later. I have left Niantic, I’m started up my own company, working on ██ █████████ ████ ████████ ████ ███ ███████ (████████! I’m announcing it next week! sneak preview!). The fatigue has gotten better and worse. At my best times, I’m able to travel into London and work in an office for a day or two or see friends - but I still have to be careful with resting before and afterwards. And there’s times when I do too much, and have crashes - the worst of which was last November, which took me back for a week or so to being unable to leave my bed for more than a few minutes at a time, and which I’m still not fully recovered from. I am giving this talk from bed, now, although I would much rather have travelled out to SF, and be hanging out with all of you in Yerba Buena Gardens eating icecream.

What was helpful

So. Let me talk about some of the specific things that have helped me.

First up, just an obvious thing

Medical insurance

I’m not going to go on about the difference between US and UK healthcare systems, but I do want to state the obvious and say that not having to worry about access to healthcare is a big thing. Do what you can to make sure people don’t have to stress about this. even outside of the US that might mean health insurance! Although I will say that Niantic had good coverage… but it would only cover diagnosing a chronic condition, and would stop as soon as that happened. And I’ll say that the NHS is also bad at covering this stuff - literally yesterday I was on the phone, still trying to chase up a referral to a rheumatologist to get a diagnosis, years into this. So… it’s not easy, and chasing up healthcare can be a job in itself.

What else?

Paid sick leave

I should say that the norms in the UK are much more generous than in the US. Here, sick leave is counted separately from holiday, and everywhere I have worked has had an allocation of paid sick leave, which (until this happened) I had never had to worry about the duration of.

This is crucial. In the case of Long Covid specifically, being able to take time off and rest in the early days is what makes a full recovery much more likely. And worrying about the financial hit is what pushes people back to work before they’re ready. Before they ought to.

And I’d say as well that time off is not just limited to times when people are too ill to work, but also about getting to medical appointments. It can helpful to track this separately, and flexibility can help a lot here if people need to take random hours here and there.

Working remotely

And working remotely, which is a thing I think everyone has had to get better at over the past couple of years. Obviously, this makes a huge difference. The energy involved in commuting, the ability to work piecemeal through the day, with rest in between, the ability to work from bed…

as helpfully modelled by Pixie here.

It sounds messed up to say, but I feel so fortunate to have fallen ill during this pandemic. Comparing my experiences with people who fell ill beforehand, I don’t think before this I would have been able to return to work remotely, don’t think friends would’ve been as up for hanging out online, I wouldn’t have been able to give this talk without having had to travel.

So, speaking of online…

let’s talk about Zoom.

Zoom Fatigue is such a real thing. Illness has made me a fine connoisseur of exactly how tiring different activities can be. And I can really tell the difference between being on Zoom with video or audio only. Just making the “I am engaged and listening to you” face! (at this point I made the face) There are actually academic studies around this that back this up1.

And I’d say as well, that scheduling meetings so people have time before and after to recover from them can be very important.

So, as I said before, after a year or so, I had improved to the point that I could occasionally come into the office. One thing that helped when I did come in was:

A Giant Plush Snorlax

and here you can see me, helpfully modelling it.

Because I was working at Niantic, we had Pokemon stuff around, including a giant plush Snorlax, of the size where you can sit/lie down on it. Because my fatigue is triggered a lot by posture, and lying down helps me a lot, being able to work lying on this giant Snorlax meant I could come in more and for longer than I would otherwise have been able to.

Now, I am not saying that you need to go buy your chronically ill employees a giant Snorlax plushy. And if I was coming in every day, I would’ve asked for a more professional setup. But the basic point here is that tailoring the office space for what people need can be helpful. Different people will need different things, be that desks, seating, computer equipment, noise cancelling headphones, whatever - ask them!

Phased return

So having a lighter schedule especially in that time when I was returning to work helped a lot. A lot of managing this illness is not being sure what your energy limits are. And if you go over them, you’re really punished for it.

So, it’s best to start with a light workload, and a light schedule, and then, if you feel up to it, slowly increase.

Reduced hours

Or this might just permanently mean working less. Either fewer hours per day, or maybe fewer days per week. I am very pleased to see an increasing number of studios bringing in a 4 day week, which seems like both a great move for the workers there generally, as well as specifically for people with chronic illnesses.

One thing that’s important to remember is that having a fatigue condition means that you have less energy overall - so even if you can still technically work fulltime, that means you’re likely cutting back a lot on things you’d be doing outside of work to keep within that energy budget. And that’s just not a good way to live.

Reducing stress

So, for me, there are broadly 3 types of things that tire me out:

- physical. Luckily we make software, so this is less present than with a lot of jobs

- mental. This definitely is present! Hard to get around this. We have to do some thinking sometimes.

- emotional. This is also a big source of fatigue. And it is something that is hard to avoid. Especially when dealing with really scary things, like fear for the future, potentially losing your income, and maybe even your source of identity.

(There’s a kind of funny thing: a booklet I saw early on gave the advice to limit your worrying to a few hours a day. Just not to get too tired out.)

So it’s worth thinking a lot about what sources of avoidable stress there are for your employees, and how you can try to reduce them, and let them save their energy for more existential terrors.

And the final thing that was helpful for me was:

Understanding

Just… knowing that you can ask for accommodations, knowing that you can go “I’m feeling out of it, I need to bail from this meeting”. That lack of judgement if you do so. That matters a lot.

But the flipside to this is that you don’t have a right to know everything that’s going on with your employees. They should be able to have space to have work be about work not about their illness. So. Understanding, but without prying.

OK, but what about people who aren’t me?

So. This has been some stuff that was helpful for me. But what about people who aren’t me? Who don’t have my particular condition. Who work in a different workplace.

Well, I already kind of gave you the answer up top. There’s a lot of different illnesses, and a lot of different people experiencing those illnesses in different ways. So, I’m sorry to say:

Ask them

They will know what they need much better than I can guess at. Your workplace will be different to mine, I can’t give you a perfect answer. Ask them.

[this next bit was cut for time! but you get to see it. bonus content!]

But ok ok, I’ll try to be useful. Here’s a few more examples for various conditions:

For people with Irritable Bowel Syndrome or Crohn’s disease, if they’re in the office, it can be helpful to provide sufficient access to toilets. This can also be something that affects people more or less at different times of the day, so it’s also helpful to be flexible in terms of working hours. It’s also worth considering that commuting in can be a anxious time, in terms of limited toilet access - shifting working hours can avoid rush hour, or maybe it’s more important for them to be able to drive in.

For people with chronic migraines, again, different times of day can be better or worse. Shifting work hours can help avoid the worst times. And if people are in the office, see what you can do to remove triggers. For example, if they’re set off by scents you can remove air fresheners, swap scented soap for unscented, ask people to stop wearing perfume in. If it’s triggered by noise, then maybe they want to move desks to somewhere quieter, or try to dampen noise. if it’s lighting then maybe swapping light fittings can help.

If you have diabetes, then you might need to inject insulin, which some people are very understandably not keen to do in public spaces. It can also be important to eat on a regular and predictable schedule - which means doing things like making sure a meeting doesn’t overrun into lunch can be important.

But for a lot of these diseases - it’s the same kind of thing that’s needed. Providing flexibility, working to try to adjust the workplace so that it fits their needs better, giving people slack to take care of themselves.

So this is the part of the talk where I want to get a bit more real. If you’re here at this session I am going to take it for granted that you want to support employees who are dealing with chronic illness. And why you might want to do that is pretty clear - ie, it makes their lives better, and that’s a good thing. So I want to flip this around, and ask the harder question.

Why don’t people get the support they need?

And I don’t want to assume that it’s just down to people being evil, cackling away in their lairs as their coworkers go through difficult times. People want to help people… and they want to think of themselves as the kinds of people who help people… but good intentions are not always enough.

So why does this happen? Let’s dig into some of the reasons, and see if we can break them down a bit.

Reason one:

It’s expensive.

I’ve described some fairly good treatment from my old employer, Niantic. But I do want to acknowledge here that Niantic is a large company with a lot of money, and most small studios… have less money. I definitely have sympathy for people who are looking at a tight budget, trying to make things work, and then finding that a core part of the team is not going to be able to work at full capacity for a while. Or ever, maybe.

But there’s two things I’d say to this.

First off:

…But it’s the law

it’s the law. In the UK, it’s the Equality Act of 2010, which says that, if you have an employee who has a disability, you are required to make “reasonable adjustments” to enable that employee to work.

And in the US, there’s an equivalent provision in the ADA, which says that employers are obliged to offer accommodations unless that would impose an “undue hardship.”

And I think there are similar laws in many other countries around the world. Now both have a reasonableness test, which means that you’re not forced to make these accommodations if it’s going to bankrupt you, but you do have try.

And for the other reason, I’m going to be a bit cynical here for a second. Making these adjustments might be painful. But that means

It’s… an opportunity?

An advantage that small studios have over larger companies is that they can be much more flexible and respond to the needs of their workforce. You don’t have to worry about making a single policy work for thousands of people, managing all the exceptions that can create - you know the people you’re working with, and you can adapt how you work to fit them.

And… there’s lots of people out there who have these kinds of invisible disabilities, who can’t fit into a regular in-the-office 9-5 type schedule, who have tried that and found it doesn’t work for them. And, a lot of them are really talented. So, by making your workplace somewhere where they can thrive and be happy, you can (and again, apologies for being really cynical here) hire a level of talent you might not otherwise be able to afford. Because what they value is a workplace where they can work. And work sustainably, and which supports them to have a life outside of it.

And I’d say as well, these people often have another skill that can be undervalued in the workplace, which is pacing themselves and setting boundaries and knowing what their limits are.

Ok, so, next reason you might shy away. And here we’re getting a bit closer to the bone.

It seems unfair

So maybe it seems unfair. You maybe have a little niggle in the back of your mind, like – if I put this stuff in place for one person, then how am I going to explain it to everyone else? How come one employee gets this stuff and other people don’t?

Or maybe it’s more than that. Maybe the reason is actually

You’re jealous

Maybe you’ve been listening to this talk, hearing me talk about working 4 day weeks, taking time off to recover from things, lying on a big Snorlax plushy… and you’ve thought… damn, I’d quite like that myself. How come they get that stuff and I don’t?

And to this I say. Yeah. That’s fair. And if you’re finding yourself with this kind of reaction, then

You deserve better too

Like, maybe you’re starting to get a bit burnt out? Maybe you deserve a better work/life balance. And it’s worth just really reflecting on this point, really sitting with any of this discomfort you might feel, any twinges of unfairness you might have. and really reflecting on changes you can make to make your working conditions better, and changes that might make conditions better for everyone who works there. There’s nothing saying that good conditions should only be for people who have a disability.

Everyone deserves better, too

Disability is not an unique thing, it’s part of the spectrum of human needs. Different people need different things in order to be happy and healthy at work. Parents need time off and flexibility for kid stuff. People going through war, people who have suffered a death in the family, people who are dealing with burnout, people whose cats got ill and they need to take them to the vet. People are people, and they have whole lives. And… you don’t deserve to hear about their whole lives, but you should try to give them the space and flexibility that they need.

So this brings us onto the final reason you might not put these accommodations in place

You don’t know they have it.

They haven’t disclosed their disabilities to you. So. Why not? Why wouldn’t they? This talk has been about the positive side of this, what you can do to support people who have disabilities, but on the flipside of this is that people can look at you differently when they learn about your disability. I was hesitant to give this talk, because I knew I would be here talking to a lot of people and being public about my weaknesses. About the ways that I am maybe a little more awkward to employ. And you can’t unring that bell! You can’t take it back, you can’t transform yourself back into someone who isn’t looked at in a different way, maybe with pity or concern.

And I want you to take a moment, and just seriously consider that someone you work with does have an illness that they struggle with, and is concealing that from you because of fear of the consequences of disclosure. Does that seem possible? Can you think of some reasons they maybe wouldn’t be coming forwards?

So. How do you build an environment where people feel like they can come to you and talk about any illnesses they have. Any changes they need. There’s a ton that goes into this, and more than I can talk about here, but fundamentally it comes down to a single word:

Trust.

And this is about the big things, yes, but it’s also about the small things. Do you keep your word about things you casually promise? Are you sometimes dismissive about people’s reasons why they might be late in or struggling with something. Do you take people’s minor problems seriously, or do you dismiss them or brush them off? Can you be trusted to keep a confidence? If someone tells you about a thing they’re struggling with, can they trust you to keep it to yourself, or is it going to spread around the studio? Being a leader, being someone with power over others, that means those people study you intently, and are very motivated to learn exactly what they can expect from you, and what trust they can safely place in you. So: what messages are you sending them?

OK OK OK. So. Let’s sum up.

Summing up

- paid time off

- flexible working times

- working remotely

- or, adjusting the office environment

- reduce stress

There’s a lot of specific things you can do to help people with invisible and chronic illnesses. Some of the big ones are giving people sick leave, giving people time for medical appointments, giving people flexibility with the timing and number of hours worked - do they need to come in late, or work part time, or what. Letting people work from home is a huge thing that is really revolutionising access to the workplace. but if people are coming in, what can you do to make the office environment less hostile to them? Maybe that’s a giant Snorlax. And just generally what can you do to remove unnecessary stress from people’s working lives? where are they carrying a load they don’t have to?

But more fundamentally, the things people with chronic illnesses need are just more enhanced versions of what everyone needs.

- ask people what they need

- build an environment of trust

Everyone has different access needs, and the most important thing you can do to meet those needs is to ask them what they are. But in order to have that conversation, you need to build a relationship where they will trust you. Trust that you will take this seriously, and trust that you’re on their side.

-FIN–

22 March 2022